(including Afforestation, Agricultural Reclamation, Burning, Dumping, Erosion, Overgrazing, Tourism Trampling and Wind Farm Construction)

Habitat loss and fragmentation have grave consequences for peatland biodiversity conservation. The changes come about when one habitat type is removed and replaced by another or when land use activities cause degradation of the quality of the habitat and species composition. The loss of peatland habitat has been more rapid in the past 50 years than ever before in human history. Continued human disturbance of peatland habitats is increasing their extinction rates.

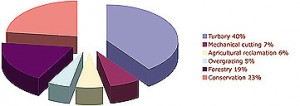

Peatland Utilisation in Ireland

In Ireland turbary and mechanical cutting have resulted in a 47% loss of peatland habitats. These losses of habitat are dealt with in the section on Over-Exploitation. Drainage and burning are integral destructive forces in the early stages of peat extraction.

As well as turf cutting there are a wide range of uses for peatlands which are causing serious habitat losses (see piechart inset) such as forestry (19% loss), overgrazing (5% loss) and agricultural reclamation (6% loss). Forestry and agricultural reclamation involve drainage and fertilisation, which have immediate negative impacts on the hydrology and nutrient status of the host peatland.

Other uses of peatlands cause degradation of sites such as dumping, burning, quarrying, wind farm installations, tourism impacts (trampling) and infrastructure developments including roads, electricity pylons, telephone masts and gas pipelines.

Peatland utilisation in the Republic of Ireland.

Peatland utilisation in the Republic of Ireland.

Source: IPCC’s Peatland Sites Database 2009

According to the State of the Irish Environment (2004) published by the Environmental Protection Agency, in the ten year period between 1990 and 2000, 76,000ha of peatland had changed from wetland habitat to a transitional woodland / scrub habitat which represents 6.5% of the original area of peatland in Ireland.

The loss of peatland habitat is further reflected in the loss in range and breeding populations of peatland birds. The 2008 Birds of Conservation Concern in Ireland report produced by Birdwatch Ireland and the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) includes four peatland birds on the Red List including Red Grouse, Curlew, Golden Plover and Lapwing, further evidence of the continued loss and degradation of habitat and whole sites. The change of habit of the Greenland White-fronted Goose from using peatlands as over-wintering sites to the Wexford Slobs is thought to be due to the loss of peatlands throughout the country.

The National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) have completed a report entitled Assessment, Monitoring and Reporting under Article 17 of the Habitats Directive (Anonymous, 2006). In this report the main pressures on peatland habitats are listed in the table below.

Table listing the main pressures on peatland habitats as identified by the National Parks and Wildlife Service (2006).

|

peat extraction |

mechanical peat extraction |

hand cutting |

wind farm development |

|

land reclamation |

drainage |

burning |

grazing |

|

overgrazing |

erosion |

forestry planting |

forestry management |

|

improved access to site |

roads |

motorways |

disposal of household waste |

|

quarries |

water pollution |

restructuring agricultural land holdings |

land fill |

|

infilling |

invasion by a species |

dispersed habitation |

electricity lines |

|

walking |

horse-riding |

use of non-motorised vehicles |

climate change |

IPCC monitors 736 peatland sites in the Republic of Ireland that have a biodiversity conservation value locally, nationally and internationally. We monitor damage and threats to each site. Each issue leading to habitat loss or degradation will be dealt with in the following sections and the threats to the sites of biodiversity value will be quantified.

Afforestation on Peatlands

The driver for the historical loss of 19% of the original area of peatland to forestry was based on the Government policy of large scale afforestation. In the 1990’s a target of 20,000ha of planting per year was set in the Strategic Plan for the development of the forest sector in Ireland. Ultimately the Government intend to plant 17% of the land area of Ireland by 2030 (Forest Service, 1996). To date, 218,850ha of blanket bog and 6,175ha of raised bog have been afforested. Approximately 80% of this is managed by Coillte, the state owned forestry company (Farrell and Renu-Wilson, 2008). Since 1980 an estimated 86,000ha of peatlands has been planted on privately owned land. These schemes were funded under the Forest Service grant schemes.

In meeting Government planting targets, the Forest Service administer a grant scheme to private individuals for forestry planting. The Forest Service does not have a specific policy in relation to peatland afforestation. Their policy in relation to peatlands, and other land types, is primarily concerned with their suitability for afforestation taking into consideration soil type, soil fertility, exposure, elevation, access, landscape and conservation status. The Forest Service have no prohibition against planting on deep peat and their grant scheme is now the main source of afforestation on blanket bog. 4,000ha of peatland were afforested in 2006 under this scheme (Black et al, 2008). While this scheme screens against designated sites and areas of deep peat, there are a growing number of locally important biodiversity sites that are threatened. In addition, forestry in the wider countryside needs to be planned with biodiversity conservation, climate change and economic returns in mind. All commercial and private afforestation schemes should comply with the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) forest certification process until such time as the Irish Forest Certification Initiative (IFCI) is completed. This aims to promote environmentally, socially and economically sustainable forest management.

In meeting Government planting targets, the Forest Service administer a grant scheme to private individuals for forestry planting. The Forest Service does not have a specific policy in relation to peatland afforestation. Their policy in relation to peatlands, and other land types, is primarily concerned with their suitability for afforestation taking into consideration soil type, soil fertility, exposure, elevation, access, landscape and conservation status. The Forest Service have no prohibition against planting on deep peat and their grant scheme is now the main source of afforestation on blanket bog. 4,000ha of peatland were afforested in 2006 under this scheme (Black et al, 2008). While this scheme screens against designated sites and areas of deep peat, there are a growing number of locally important biodiversity sites that are threatened. In addition, forestry in the wider countryside needs to be planned with biodiversity conservation, climate change and economic returns in mind. All commercial and private afforestation schemes should comply with the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) forest certification process until such time as the Irish Forest Certification Initiative (IFCI) is completed. This aims to promote environmentally, socially and economically sustainable forest management.

The table below shows that out of IPCC’s database of 736 conservation worthy peatlands, 194 sites have been partially afforested. Only 28 sites have been restored by Coillte to date with financial assistance from the EU Life funds. As afforestation has serious impacts on peatland hydrology, carbon function, species composition and nutrient status, restoration of all affected sites of conservation concern in Coillte’s ownership and privately owned should be a priority.

The table shows the number of peatland sites of conservation importance in the Republic of Ireland that have been damaged or threatened by afforestation. Source: IPCC Sites Database 2009.

| Peatland Habitat Status | Number of Sites |

| SAC | 88 (includes 28 afforested sites where restoration work has begun by Coillte) |

| NHA | 92 |

| Undesignated local biodiversity areas | 14 |

| Total number of sites damaged by afforestation | 194 |

The priority actions for tackling the issue of afforestation on peatlands in the Republic of Ireland are set out in the table below:

| Actions Needed to Control Afforestation on Peatlands | Priority | Timescale On-going Short (0-3 years) Medium (3-5 years) Long (5-10 years) |

| Afforestation should be prohibited on all peat soils. | High | Short |

| The Forest Service should stop all grant aided afforestation on peatlands. | High | Short |

| Afforested peat soils when harvested should not bereplanted with trees, but restored to peat accumulating systems using the methodologies and best practice established throughout the EU and globally. | High | Long |

| Ensure that in the revision of the 1946 Forestry Act, the obligation to replant on afforested peatlands is waived. These cleared sites should be restored. | Medium | Medium |

| Complete the preparation of a National Forest Standard for Ireland. | High | Medium |

Agricultural Reclamation

Peatlands in Ireland have been reclaimed for agriculture for centuries. The Peat Enquiry Committee in 1917 (Anonymous, 1921) observed that large areas of cutaway and cutover bog had already been reclaimed for agriculture. The reclamation method usually included “marling” or mixing of sea sand or domestic fuel ash with the top 15-20cm of peat.

Agricultural reclamation usually results in the total elimination of the resident peatland flora and fauna. Peatland types which are reclaimed for agriculture consist of cutover and cutaway raised bog habitat, cutover and cutaway blanket bog habitat and fen habitats. The process of reclamation involves drainage, removal of peat and fertilisation.

Land drainage and reclamation has been supported over the years by several Acts and Schemes including the 1945 Arterial Drainage Act, the Land Project of 1949, the Farm Modernisation Scheme 1974-1985, the Western Drainage Package 1979-1988, the Farm Improvement Programme and the Programme for Western Development.

It is not uncommon to see agricultural reclamation in the cutover areas surrounding designated sites. Farmers reclaim small field plots within the hydrological basin of the peatland when turf cutting has ceased. There is an annual application of fertiliser to bring some productivity to the land. This causes problems if there is run off into waterways or eutrophication. In the longer term further problems arise when reclaimed peatland provides sites for housing or other buildings or infrastructure, as it restricts any future attempt at restoring the hydrological unit of the site. The table inset shows that over 15% of peatlands in IPCC’s database are affected by agricultural reclamation.

The table shows the number of peatland sites of conservation importance in the Republic of Ireland that have been damaged or threatened by agricultural reclamation. Source: IPCC Sites Database 2009.

| Peatland Habitat Status | Number of Sites |

| SAC | 45 |

| NHA | 56 |

| Undesignated local biodiversity areas | 33 |

| Total number of sites damaged by agricultural reclamation | 134 |

The priority actions for tackling the issue of afforestation on peatlands in the Republic of Ireland are set out in the table below:

| Actions Needed to Control Agricultural Reclamation on Peatlands | Priority | Timescale On-going Short (0-3 years) Medium (3-5 years) Long (5-10 years) |

| Implement sustainable farming regimes in farming areas of high biodiversity value. | High | On-going |

| No peatland sites should be reclaimed for agriculture | High | On-going |

| Where possible, peatland sites damaged by agricultural activities or reclamation should be restored be peat accumulating habitats. | High | Long |

Burning

The damage to a peatland by burning depends on the intensity and frequency of burning. Many of the rare and sensitive plants found on peatlands cannot survive fires. Burning decreases the cover of Sphagnum and so decreases the capacity to generate new peat.

Burning is a frequent activity on raised bogs and is mainly related to turf cutting. 199 peatlands of conservation importance in the Republic of Ireland are threatened by burning (see table inset). According to Fernandez et al. (2005) burning occurred on 24 of 48 raised bogs surveyed in a ten year reporting period. The burning was mainly associated with peat extraction and so was more frequent in those sites with a high intensity of turf cutting where the vegetation was burnt to accommodate cutting. The regular burning of peatlands leads to the release of large amounts of carbon, which has been built up and stored in peatlands over thousands of years.

Burning is a frequent activity on raised bogs and is mainly related to turf cutting. 199 peatlands of conservation importance in the Republic of Ireland are threatened by burning (see table inset). According to Fernandez et al. (2005) burning occurred on 24 of 48 raised bogs surveyed in a ten year reporting period. The burning was mainly associated with peat extraction and so was more frequent in those sites with a high intensity of turf cutting where the vegetation was burnt to accommodate cutting. The regular burning of peatlands leads to the release of large amounts of carbon, which has been built up and stored in peatlands over thousands of years.

Controlled burning on blanket bog is traditionally carried out to promote new heather growth for sheep grazing or for Red Grouse. However, if this activity is not done properly it can be destructive. Species such as Red Grouse have declined partially due to lack of skill and understanding in the use of this management practice. The Muirburn Code is regarded as best practice in using fire for managing peatlands. However, a management study for peatlands in Caithness and Sutherland recommended no burning on wet intact blanket peat habitats where heather growth is naturally stunted (SNH 2005).

The table shows the number of peatland sites of conservation importance in the Republic of Ireland that have been damaged by burning. Source: IPCC Sites Database 2009.

| Peatland Habitat Status | Number of Sites |

| SAC | 78 |

| NHA | 104 |

| Undesignated local biodiversity areas | 17 |

| Total number of sites damaged by burning | 199 |

The priority actions for tackling the issue of dumping on peatlands in the Republic of Ireland are set out in the table below:

| Actions Needed to Control Burning on Peatlands | Priority | Timescale On-going Short (0-3 years) Medium (3-5 years) Long (5-10 years) |

| Burning of raised bog and blanket bog habitat should be prohibited. | High | On-going |

| Strictly control burning to promote heather growth on wet and dry heath habitats. | High | On-going |

| Reduce factors which increase the risk and impact of peatland fires, such as turf cutting. | High | Medium |

| Put an early warning system in place to notify the fire brigade, local wildlife rangers and police of peatland fires. | High | On-going |

Dumping

The nature of peatland sites means that they are usually situated in sparsely populated and isolated areas. Access roads constructed on peatlands for turf cutting and wind farms have opened up peatlands and provided easy access for dumping on peatland sites. The dumping of domestic and industrial waste on peatlands is indicative of a popular attitude that peatlands are wastelands of little value other than as dumping sites or sources of fuel.

The nature of peatland sites means that they are usually situated in sparsely populated and isolated areas. Access roads constructed on peatlands for turf cutting and wind farms have opened up peatlands and provided easy access for dumping on peatland sites. The dumping of domestic and industrial waste on peatlands is indicative of a popular attitude that peatlands are wastelands of little value other than as dumping sites or sources of fuel.

Fens are often looked upon as suitable locations for the dumping of landfill because of their low-lying nature and the fact that they are unsuitable for most types of development. The objective is often to raise the level of the fen in order to improve drainage and make a site more suitable for subsequent development such as housing. The Monaghan Fen Survey found that of the 42 sites surveyed in detail 20 were found to be affected by dumping and infilling (Foss and Crushell, 2007). The IPCC peatland sites database records dumping on 65 sites (see table inset).

The table shows the number of peatland sites of conservation importance in the Republic of Ireland that have been damaged by dumping. Source: IPCC Sites Database 2009.

| Peatland Habitat Status | Number of Sites |

| SAC | 19 |

| NHA | 18 |

| Undesignated local biodiversity areas | 28 |

| Total number of sites damaged by dumping | 65 |

The priority actions for tackling the issue of dumping on peatlands in the Republic of Ireland are set out in the table below:

| Actions Needed to Control Dumping on Peatlands | Priority | Timescale On-going Short (0-3 years) Medium (3-5 years) Long (5-10 years) |

| Prosecute people who dump domestic or industrial waste on peatlands. | High | On-going |

| Report all incidences of infilling and dumping to the EPA and Local authorities. | High | On-going |

| Erect signage at all peatlands of conservation importance to make communities aware of their status. | Medium | Short |

| Access routes to peatlands should be minimal so as to avoid easy vehicle access for dumping. | Medium | Medium |

Erosion

Eroded blanket bog is characterised by exposed bare peat haggs and the underlying mineral soil. Extensive erosion on blanket bog is very rarely a natural feature and is often caused by a combination of several factors. When an eroded bog surface is coupled with naturally or man induced deep gullies, and cracks and severe climatic conditions, peat is washed away until all that is left are dried chunks of intact peat called “haggs”. With every storm, erosion removes small amounts of peat at the edge of the peat haggs and in dry periods the peat blows away with the wind. As a result of this erosion by wind and water the surviving haggs point down-slope and downwind. Damaged and eroding blanket bog can be found in every mountain range in the country (Bradshaw, 1987).

The main cause of erosion is thought to be disturbance caused by human activity and farming practices, such as turf cutting (both mechanical and hand cutting), afforestation, over-grazing, regular burning and recreational activities (Bradshaw, 1987). Mountain blanket bogs are sensitive to changes in rainfall, temperature and wind speed. An increase in rainfall coupled with more severe winters could damage the most exposed peatlands, increasing the extent of erosion.

”Bog bursts” or peat flows are a dramatic form of peat erosion. Sections of peat on sloped areas can break off from the main body of a blanket bog and flow down-slope, similar to a volcanic lava flow. Bog bursts usually happen after heavy rain on sites which have been put under human pressures, such as overgrazing, turf cutting or wind farm construction. For example, the construction of a wind farm at Derrybrien, county Galway resulted in a large bog burst causing almost half a square km of blanket bog to travel 2.5km (Lindsay and Bragg, 2005). During a bog burst it is thought that the living plant layer of the bog tears due to stress and the very wet peat centre flows under the influence of gravity. Other bog bursts have been recorded in Ben Gorm in Connemara, on Clare Island in Co. Mayo and 52 separate bog bursts have were recorded at Pollatomish, Co. Mayo.

The main cause of erosion is thought to be disturbance caused by human activity and farming practices, such as turf cutting (both mechanical and hand cutting), afforestation, over-grazing, regular burning and recreational activities (Bradshaw, 1987). Mountain blanket bogs are sensitive to changes in rainfall, temperature and wind speed. An increase in rainfall coupled with more severe winters could damage the most exposed peatlands, increasing the extent of erosion.

”Bog bursts” or peat flows are a dramatic form of peat erosion. Sections of peat on sloped areas can break off from the main body of a blanket bog and flow down-slope, similar to a volcanic lava flow. Bog bursts usually happen after heavy rain on sites which have been put under human pressures, such as overgrazing, turf cutting or wind farm construction. For example, the construction of a wind farm at Derrybrien, county Galway resulted in a large bog burst causing almost half a square km of blanket bog to travel 2.5km (Lindsay and Bragg, 2005). During a bog burst it is thought that the living plant layer of the bog tears due to stress and the very wet peat centre flows under the influence of gravity. Other bog bursts have been recorded in Ben Gorm in Connemara, on Clare Island in Co. Mayo and 52 separate bog bursts have were recorded at Pollatomish, Co. Mayo.

In raised bogs, bog bursts occur when the edges give way following intensive drainage and turf cutting. Bog bursts can lead to further erosion if the bare peat is not quickly re-colonised by plant growth.

A research strand on bog bursts is included in the EPA funded BOGLAND project. Peat soil stress tests for wind farm construction are a component of this work.

The priority actions for tackling the issue of erosion on peatlands in the Republic of Ireland are set out in the table below:

| Actions Needed to Control Erosion on Peatlands | Priority | Timescale On-going Short (0-3 years) Medium (3-5 years) Long (5-10 years) |

| Strict planning control of all developments in upland areas should be practiced including road and wind farm construction. | High | On-going |

| Wise use and management of peatlands of conservation importance and peat soils in the wider countryside should be implemented to avoid creating conditions suitable for bog bursts and erosion. | High | On-going |

| Appropriate peat soil stress tests should be implemented on any peatland soils beingconsidered for wind farm development. | High | On-going |

| Initiate a research program into rehabilitating peatlands affected by bog bursts. | Medium | Long |

Overgrazing on Peatlands

Overstocking of sheep is one of the major damaging activities affecting blanket bog habitats. Total sheep numbers increased from 3.2 million in 1980 to 8.9 million in 1992 (CSO, 2008). This increase was due to EU funded agricultural incentives. A severe overgrazing problem on blanket bog resulted from the large increase in sheep numbers, especially in the western counties of Donegal, Leitrim, Sligo, Mayo, Galway and Kerry which occurred because the land ownership of these areas was in commonage (shared ownership). However, overgrazing also occurred on privately owned peatlands. Over-grazing on blanket bog results in a decrease in vegetation cover, a depletion of bog species, invasion by species alien to the bog habitat and erosion of peat surfaces (Bleasdale 1995, MacGowan & Doyle 1996 and 1997, and McKee et al 1998). The loss of characteristic and rare flora, such as heather, sedges and mosses, deprive wildlife of food and cover and numbers of fauna may also therefore be affected, for example Red Grouse (Douglas 1998). Management of the peatlands for agriculture involved an increase in the intensity and frequency of burning which further degraded sites. Bog slides are the most severe result of overgrazing and have occurred as small piecemeal slides on several SACs such as at the Owenduff Nephin Complex in Mayo, the MacGillycuddy Reeks in Kerry, the Maumturk Mountains in Galway, the Mweelrea Sheeffry Erriff Complex in Mayo and the Twelve Bens Garraun Complex in Galway (C. Douglas NPWS pers. comm., 26 April 2009). Overgrazing can also cause large, significant bog slides such as in the Maumturk Mountains in 2006 and Clare Island in Mayo. In the Republic of Ireland 155 peatland sites of conservation importance have been damaged by overgrazing (see table inset).

The table shows the number of peatland sites of conservation importance in the Republic of Ireland that have been damaged or threatened by agricultural reclamation. Source: IPCC Sites Database 2009.

| Peatland Habitat Status | Peatland Sites Damaged by Overgrazing | Damaged peatland sites being managed by Commonage Framework Plans |

| SAC | 73 | 88 |

| NHA | 47 | 18 |

| Undesignated local biodiversity areas | 35 | 36 (34 of these are proposed NHAs) |

| Total number of sites damaged by agricultural reclamation | 155 | 142 |

In response to the severe degradation to blanket bog habitats due to overgrazing a revised and subsequently amended Rural Environmental Protection Scheme (REPS) was introduced in 1999. As a result the Government launched the Commonage Framework Plans in 2002. These plans are expert assessments of the environmental status of commonage and include recommendations, where necessary, for reductions in sheep numbers to allow vegetation to recover from the effects of overgrazing. If a farmer wishes to appeal the de-stocking rate recommended in the Commonage Framework Plan for their commonage they can appeal through the Commonage Framework Plan Appeals Board. At present a re-assessment of the Commonage Framework Plans is being carried out by the Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government. As part of this survey 30% of the national commonage framework plans are being re-assessed, in addition to all commonage plans that have a de-stocking of greater than 50%. This re-assessment is due to be completed by the end of 2009 and will provide an overview of the effectiveness of the commonage work plans in dealing with the problem of overgrazing

The results from the June 2007 agricultural survey show that the total number of sheep has fallen to 5,521,600, the lowest since 1986 (CSO, 2008). Studies have shown that once the pressure of over grazing has been removed from a peatland the vegetation recovers rapidly. For example, a long-term study to monitor the recovery of vegetation of peatland habitats following the exclusion of grazing within Ballycroy National Park was initiated in 1996 by NPWS. The study consisted of the long-term monitoring of nine grazing exclosures measuring 5m x 5m situated within the Park. The exclosures were established in areas covering a range of habitats including lowland blanket bog, upland blanket bog, montane heath and upland acid grassland.

The results of the exclosure survey indicate that the exclusion of grazing allowed for the recovery of vegetation within all of the exclosures. The rates of recovery of vegetation were variable between each exclosure and related to the level of degradation at the outset of the study and the habitat type. In some exclosures vegetation recovered within 3 to 4 years. The exclosure survey proves that rapid recovery of a variety of habitats within a peatland can be achieved once grazing pressure is removed from over grazed and eroded areas.

However, in reality sheep are rarely totally excluded from peatlands under the Commonage Framework Plans. This study is a first step in researching suitable management regimes for peatlands damaged by overgrazing. It will also be necessary to actively restore severely degraded areas within peatlands of conservation importance through, for example transplanting peatland vegetation such as heather or Sphagnum moss.

The priority actions for tackling the issue of overgrazing on peatlands in the Republic of Ireland are set out in the table below:

| Actions Needed to Control Overgrazing on Peatlands | Priority | Timescale On-going Short (0-3 years) Medium (3-5 years) Long (5-10 years) |

| Implement sustainable grazing regimes on all peatlands. | High | On-going |

| Implement the findings of the 2009 report on there-assessment of the Commonage Framework Plans | High | Short |

| Complete destocking on peatland areas that have shown no improvement following management by the Commonage Framework Plans. | High | Short |

| Undertake active management and restoration of severely damaged peat surfaces. | High | Long |

| Introduce guidelines and training for farmers to assist them in the restoration of degraded blanket bog habitats. | High | Long |

Tourism /Trampling

The growing awareness of peatland issues among the general public, and the promotion by tourist and conservation agencies of peatlands as a special interest holiday has resulted in a marked increase in the number of visitors to some of these fragile habitats, with 420,000 visitors to Ireland engaging in Hiking/Walking activities in 2007 (Anonymous, 2008a). There are demands for more access from walkers, horse-riders, cyclists, climbers, training groups and school parties. Currently Irish National Parks attract 416,000 visitors per year (www.failteireland.ie).

A national voluntary organisation called Keep Ireland Open actively campaigns for the right of recreational users to reasonable access to the Irish Countryside. They are seeking clearly marked legal rights of way, mainly in lowland areas and legal rights to allow freedom to roam in more remote and upland areas. Throughout the country, a network of peatland sites are actively being promoted for tourism, hill walking and recreational use. These include nature reserves, national parks, archaeological sites, museums and theme parks.

IPCC are concerned that some sensitive peatland habitats are being unacceptably degraded through visitor use (see table inset). This is often caused by the lack of an integrated visitor management plan for the sites in question. Peatland reserves are first and foremost, areas which are to be maintained in their natural state. If these reserves are not used wisely, the survival of crucial habitats and species will be seriously compromised.

The table shows the number of peatland sites of conservation importance in the Republic of Ireland that have been damaged by tourism/trampling. Source: IPCC Sites Database 2009.

| Peatland Habitat Status | Number of Sites |

| SAC | 6 |

| NHA | 1 |

| Undesignated local biodiversity areas | 4 |

| Total number of sites damaged by tourism/trampling | 11 |

Trampling results in decreased vegetation cover, depleted species diversity, and it allows invasion onto the affected area of species foreign to the bog habitat. Purple Moor grass (Molinia caerulea) and Bog Cotton (Eriophorum angustifolium) are more resilient bog plants to trampling in the early stages. In raised bogs trampling breaks down the bushes of Ling Heather and ploughs up the Sphagnum moss carpets.

The main plants to disappear are the ground hugging mosses and liverworts. These plants create a micro-habitat necessary for the growth of larger plants. Once this micro-habitat is destroyed the conditions for growth are changed and invasive plants then colonise these areas. Up to twenty species of these uncharacteristic plants can invade a trampled bog. Chief among these are rushes (Juncus and Luzula species) and grasses (Agrostis and Nardus species). This invasion causes serious deterioration in the vegetation that remains. The lack of vegetation in these areas also promotes peat erosion with surfaces bared to mineral soil level in places. (MacGowan & Doyle 1996, 1997 & 1998).

An example of trampling can be seen on Diamond Hill in Connemara National Park, Co. Galway where a popular walking path became severely eroded from the pressure of walkers. As the track became water logged and muddy the walker’s moved out onto the surrounding untrampled areas, thus extending the damage. As a result of this damage NPWS have constructed a board walk at Diamond Hill to reduce visitor trampling.

A countryside education programme called Leave No Trace was initiated in Ireland in 2007. This countryside code hopes to promote and inspire responsible outdoor recreation through education, research and partnerships. The programme will strive to build awareness and respect for Ireland’s natural and cultural heritage and is dedicated to creating a nationally recognised and accepted outdoor ethic that promotes personal responsibility and land stewardship (see www.leavenotraceireland.org).

The priority actions for tackling the issue of tourism trampling on peatlands in the Republic of Ireland are set out in the table below:

| Actions Needed to Control Tourism/Trampling on Peatlands | Priority | Timescale On-going Short (0-3 years) Medium (3-5 years) Long (5-10 years) |

| Manage visitors so as to avoid habitat degradation in peatland areas through education. | High | On-going |

| Construct boardwalks or trails to minimise visitor damage. Use indigenous materials where possible. | Medium | Long |

| Undertake restoration of eroded / trampled areas within peatlands of conservation importance. | High | Medium |

Wind Farms on Peatlands

Faced by increased energy costs and greenhouse gas emission constraints, Ireland is aiming to create a low-carbon economy using fewer fossil fuels and increasing the use of renewable energy sources to generate electricity. The Government has established ambitious targets for the contribution of renewables to power generation; 33% by 2020 exceeding the EU’s target for Ireland of 20% by 2020. Currently 65 wind farms, with a combined output of 803 MW, are in operation in the Republic of Ireland and additional projects are under consideration by planning authorities throughout the country. National policy places a strong emphasis on wind in meeting Ireland’s future energy needs. In the National Climate Change Strategy 2007-2012 the Government have set out ambitious targets of 15% of electricity to be generated from renewable sources by 2010 and 33% by 2020. Wind energy will be the largest renewable energy type used to meet this target.

The IPCC recognise the importance of increasing the renewable energy sector as part of international efforts to combat climate change and reduce dependency on the abstraction of non-renewable resources such as peat and oil. However, IPCC cannot support the construction of wind farms on intact peatlands including lowland blanket bog, upland blanket bog and heath habitats. There is a very significant overlap between sensitive upland blanket bog areas and areas of highest average annual wind speeds, which have a high potential to produce wind energy. These sensitive upland peatland areas have been targeted for wind farm development. The main damaging activities to blanket bogs from the construction of wind farms include the construction of an associated road network across the peatland, service structures, drainage, soil conduits for power cables, turbine foundations and electricity pylons. The construction of a new road network opens the peatland up for a range of damaging activities such as dumping of household waste, accidental fires, peat extraction or placement of grazing stock (Anonymous, 2006).

The IPCC recognise the importance of increasing the renewable energy sector as part of international efforts to combat climate change and reduce dependency on the abstraction of non-renewable resources such as peat and oil. However, IPCC cannot support the construction of wind farms on intact peatlands including lowland blanket bog, upland blanket bog and heath habitats. There is a very significant overlap between sensitive upland blanket bog areas and areas of highest average annual wind speeds, which have a high potential to produce wind energy. These sensitive upland peatland areas have been targeted for wind farm development. The main damaging activities to blanket bogs from the construction of wind farms include the construction of an associated road network across the peatland, service structures, drainage, soil conduits for power cables, turbine foundations and electricity pylons. The construction of a new road network opens the peatland up for a range of damaging activities such as dumping of household waste, accidental fires, peat extraction or placement of grazing stock (Anonymous, 2006).

Other negative impacts of wind farms constructed on peat soils include the release of large amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere during installation of wind farms, contributing to climate change. Peatlands act as carbon sinks holding the bulk of Ireland’s carbon store, which is locked up in the peat soil. The construction of wind turbines on peatlands causes desiccation of the peat soil and so upsets the carbon accumulation process and leads to an increase in the amount of carbon dioxide released to the atmosphere from the peatland.

The threat of wind farm development to blanket bog habitats was assessed as part of the Assessment of priority habitats and species carried out by the NPWS (2006). They reported that 39 of 56 wind farms surveyed were located on blanket bog. Out of the 39 wind farms, 20 have been constructed on relatively intact blanket bog. Although blanket bog habitat included in designated sites are currently less affected by wind farm developments, on numerous occasions wind farms are located at the edge of designated sites and may have significant impacts on the status of the blanket bog. Additionally, wind farms have had serious impacts on undesignated blanket bogs and this is considered an increasing threat in the wider countryside (Anonymous, 2006).

The Department of Environment, Heritage and Local Government published Wind Energy Development Guidelines for Planning Authorities, 2006. The purpose of these guidelines is to provide advice to planning authorities on planning for wind energy through the development plan process. These guidelines include revised material in relation to natural habitats, including birds and other species. While peatlands which are designated as SAC’s or NHA’s are protected for nature conservation, developments such as wind farms are not automatically prohibited within the boundaries of a designated site. This results in planning applications applying for the construction of wind farms on designated peatland sites (see tables 4.9 and 4.10). Examples include the application in 2007 for a 12 turbine wind farm in Arroo Mountain SAC 1403, which was refused planning permission by both Leitrim County Council and An Bord Pleanála.

IPCC have noted several incidences of bog bursts occurring during the construction of wind farms and their associated works, such as road construction on deep peat. Bog bursts associated with wind farm construction in recent years have occurred at Derrybrien, Co. Galway in 2003; Stacks Mountains, Co. Kerry in 2008; Carrane Hill Bog in 2008 and the Corrie Mountains, Co Leitrim in 2008 (C. Douglas NPWS pers. comm., 26 April 2009). Bog bursts not only destroy the peatland habitat present but they also pose a massive risk to drinking water supplies, cause juvenile fish kills and destruction of the aquatic environment when the displaced peat enters local water courses.

Bog bursts associated with wind farm construction are caused by a lack of adequate peat stress testing during the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA). Often an EIA for a wind farm does not assess the impacts of construction of the wind farm ancillary works of peat extraction and road construction, as the planning authorities state that these minor aspects of the project do not require assessment. However, the recent bog bursts in the Stack Mountains and Corrie Mountains were both caused by wind farm road construction. Ireland was prosecuted by the European Courts in 2008 over its handling of road construction for wind farms on bogs. The courts found that Ireland consistently failed to conduct Environmental Assessments correctly, leading to consequences such as the Derrybrien bog-slide in County Galway. The BOGLAND project commissioned by the EPA is due to provide guidelines for developers which will hopefully redress this issue in 2009.

The table shows the number of peatland sites of conservation importance in the Republic of Ireland that have been damaged or threatened by wind farms. Source: IPCC Sites Database 2009.

| Peatland Habitat Status | Peatland Sites Threatened by Wind Farms | Number of Peatland Sites Damaged by Wind Farms |

| SAC | 14 | 0 |

| NHA | 14 | 6 |

| Undesignated local biodiversity areas | 0 | 1 |

| Total number of sites damaged by agricultural reclamation | 28 | 7 |

The priority actions for tackling the issue of wind farms on peatlands in the Republic of Ireland are set out in the table below:

| Actions Needed to Control the Construction of Wind Farms on Peatlands | Priority | Timescale On-going Short (0-3 years) Medium (3-5 years) Long (5-10 years) |

| No wind farms should be placed on intact peat soils within designated sites or in the wider countryside. | High | On-going |

| Where wind farms have been placed on peatland soils the hydrology of the development site should be managed so that any negative affects do not impact surrounding peatlands. | Medium | Long |

| Implement the findings of the BOGLAND project in relation to peat stress tests for wind farm developments. | High | Medium |

Source Citation

Malone, S. and O’Connell, C. (2009) Ireland’s Peatland Conservation Action Plan 2020 – halting the loss of peatland biodiversity. Irish Peatland Conservation Council, Kildare.

Expanding on the Content of the IPCC Action Plan 2020

Please follow the links below to further information from the IPCC Action Plan 2020.

Purchase

Copies of Ireland’s Peatland Conservation Action Plan 2020 – halting the loss of peatland biodiversity cost €25 and may be ordered from the Nature Shop

Text, Photographs and Images © Irish Peatland Conservation Council, Bog of Allen Nature Centre, Lullymore, Rathangan, Co. Kildare. Email: bogs@ipcc.ie; Tel: +353-45-860133.