With colourful, fluid-filled leaves, pungent scents, glistening glue or grasping tentacles, they lure their victims to a nasty end. Carnivorous plants are unique in that they attract, trap and derive benefit from digesting their prey, and they live right here in Ireland.

Visit the Bog of Allen Nature Centre to see our living exhibition of insect-eating, carnivorous plants in the Flytraps House.

Watch the video below about the fly trapping carnivorous plants of bogs

Read a fact sheet about carnivorous plants

Carnivorous plants are a feature of bogland habitats. There are so few nutrients present in the bog that these plants have developed a taste for insects. The carnivorous plants are both active and passive.

Active trappers (they having moving parts to help to catch their prey) include:

- Sundew

- Venus Fly Trap

- Butterwort

- Bladderwort

Passive trappers (they do not move to catch prey) include:

- Pitcher Plant

- Cobra Lily

Anyone who has walked over a bog on a still, hot day will know what a paradise they are for insects, especially the biting sort. The plants there have turned the tables on the insect world and will capture, kill and eat every midge, bug and ant they can.If you’re an insect, ranging in size from a tiny water flea to a damselfly, crossing a bog or swimming in a pool can literally be a matter of life or death. For amongst the mosses and heathers, or floating in shallow pools, grow sticky traps and vacuums of death. Patiently awaiting their next victim are the passive murderers; Sundews, Butterworts and Bladderworts. They rely not on strength to catch their prey, but on the lure of beauty and desire. These are carnivorous plants, a specialised group adapted to growing in nutrient poor environments. After securing their prey with the strongest glues and fastest vacuums in the natural world, they obtain nutrients from a diet of insect flesh and juices.

Ten native species grow wild in Ireland, along with the introduced pitcher plant;

Sundews

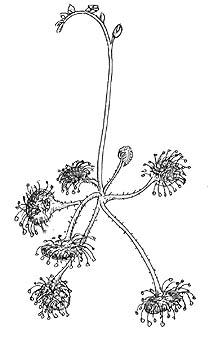

Sundews have spoon-shaped leaves which are covered with up to 200 pin-shaped red “tentacles” (or stalked glands) which respond to touch. The head of each gland is covered with a mucilaginous secretion which is acidic and enzymatic and does not evaporate. Insects may mistake the glistening leaves for nectar or may be caught because they blunder onto the leaves by chance.

On average, a sundew plant traps up to five insects per month. The prey caught includes small flies, midges, beetles and ants, although larger prey such as damselflies can also become trapped by several leaves simultaneously. The plants benefit by absorbing mineral nutrients from their prey, especially nitrogen and phosphorus which are in short supply in bogs.

When an insect is trapped by a sundew tentacle, the movements, which are electrically signalled, cause other tentacles to bend towards it and within three minutes there is no escape for the insect. The whole leaf bends over and closes up. This may take a day to complete.

Once secure, digestive juices are released to kill, then dissolve the struggling insect, a process lasting from hours to a few days. When the leaf reopens and the black remains of the inedible leg and wing pieces are seen, evidence of the plant’s way of life.

| Long-leaved Sundew. Each red tentacle on a Sundew leaf has a glandular tip that produces a droplet of “dew” which combines the adhesion of super glue with the corrosive power of battery acid. |  |

There are three species of sundew on Irish bogs which may be distinguished from one another, by the shape of their leaves. The Round-leaved Sundew Drosera rotundifolia is most common, being found almost wherever Sphagnum moss grows. The Intermediate Sundew D. intermedia is local in the west of Ireland, typically growing in clumps on bare, exposed peat. Finally, the Long-leaved Sundew D. anglica, commonly grows in permanent pools on the bog.

In all species, the reddish leaves form a basal rosette, out of which arises a flowering stem with tiny white flowers. In the winter, when food is scarce the leaves die back to form a tight resting bud.

| Sundews use “glue” to catch an insect. The insect is trapped by the tentacles and engulfed as the modified leaf gradually closes up over it. A sundew traps up to five insects per month. |

Butterworts

Butterworts derive their name from the greasy butter-like feel of their leaves. Three species occur in Ireland.

The Common Butterwort Pinguicula vulgaris, and the Large-flowered Butterwort P. grandiflora have ground-hugging, star-like leaf rosettes measuring up to 8cm across. Their beautiful mauve, violet-like flowers in early summer detract from the murder weapons below. The smaller Pale Butterwort P. lusitanica, measures only 1-2cm across and produces tiny pale pink flowers all summer.

All butterworts grow in acid bogs, fens and occasionally on wet rocks, but none is particularly common, however the great butterwort (Pinguicula grandiflora), found in the mountains and bogs of Cork and Kerry is the most conspicuous. Insects walk or fly onto the leaves, which roll at their edges to prevent escape – an unlikely occurrence – since butterworts possess the strongest natural glues known. After digestion the dry insect husk blows away. Butterworts overwinter as rootless resting buds.

Bladderworts

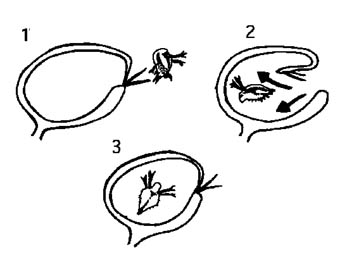

Bladderworts are easily overlooked, living in shallow pools and streams, their name derives from the tiny bladder-like traps on their feathery leaf stems. They are rootless, free-floating aquatics.

Four species occur in Ireland; the Common Bladderwort Utricularia vulgaris, Intermediate Bladderwort U. intermedia, Southern Bladderwort U. australis and the Lesser Bladderwort U. minor. None are common and all are difficult to identify.

The flowers are yellow, often showy and held on tall stems above the submerged leaves.

The bladder traps which are up to 5mm in diameter are activated by tiny trigger-hairs at the entrance to the trap. On touching these trigger hairs insects are sucked into the trap by a vacuum at speeds of up to 1/15,000th of a second. Digestive juices released inside the bladders absorb nutrients before the empty insect husk is ejected. Glands inside the bladders then absorb water out of the interior to create a vacuum and thus reset the trap.

In winter the vegetative parts of the plant die back to form tight buds, which sink to the bottom of the pool. These can be caught up in currents and dispersed to new areas of the bog.

Pitcher Plants

In 1906 the Canadian Pitcher Plant Sarracenia purpurea was introduced to Ireland. Initially it was planted on a bog in Co. Roscommon. Since then it has been transplanted onto a dozen bogs throughout the country. The leaves of the Pitcher Plant are upright and tubular in shape, and function as pitchers in that they hold rain water, hence their common name. The green pitchers have dramatic red and purple vein markings. They form cabbage-like rosettes on bogs. The flowering stem arises out of the middle of a rosette of leaves.

Pitcher plants are sophisticated invertebrate traps. First the insect is lured to the rim of the pitchers by attractive meaty-coloured patterns, and by tempting droplets of nectar. When the insect lands, it soon loses its footing on the slippery ridges around the throat of the pitcher, helped by hairs which point downward preventing its escape. Insects drown in a watery grave containing digestive juices and detergents for penetrating the microscopic breathing holes along the sides of an insect’s body.

The plant increases its chances of making a successful catch by spicing its nectar with intoxicating narcotic, so that the insects roll around in a drunken stupor. The walls of the pitcher are lined with slippery cells, and with no foothold to grab onto, the prisoner slowly falls into the watery depths of the pitcher.

| Pitcher Plants were introduced to Ireland in 1906 from Canada. Their fluid-filled pitchers are fatally attractive to visitors |

Pitcher Plants catch a wide range of invertebrates. A single pitcher naturalised in an Irish bog was found to contain 205 prey items, mainly mites, but also caddis flies, midges, beetles, small parasitic wasps and spiders.

The presence of carnivorous plants on bogs shows an interesting adaptation to a habitat that is starved of nutrients. These plants have intrigued naturalists from the time of Charles Darwin to the present day.

| Table of Carnivorous Plants Occurring in Ireland | ||

| Common English Name | Latin Name | Irish Name |

| Common Bladderwort | Utricularia vulgaris | Lus an Bhorraigh |

| Intermediate Bladderwort | Utricularia intermedia | Lus Borraigh Gaelach |

| Southern Bladderwort | Utricularia australis | Lus Borraigh Mór |

| Lesser Bladderwort | Utricularia minor | Borraigh Beag |

| Common Butterwort | Pinguicula vulgaris | Bodánn Meascáin |

| Pale Butterwort | Pinguicula lusitanica | Leith Uisce Beag |

| Great Butterwort | Pinguicula grandiflora | Leith Uisce |

| Canadian Pitcher Plant | Sarracenia purpurea | Ascaid |

| Round-leaved Sundew | Drosera rotundifolia | Drúchtín Móna |

| Intermediate Sundew | Drosera intermedia | Cailís Mhuire |

| Long-leaved Sundew | Drosera anglica | Cailís Mhuire Mhór |

Threats to Carnivorous Plants

Habitat loss is the main threat to carnivorous plants mainly from land reclamation, drainage and turf cutting. Nutrient enrichment of water and land is another threat because it increases the competition from other vegetation which shades out the carnivorous plants. Planting non native carnivorous plants in the wild boglands is not a good idea as they replace our wild bog species which are on the decline in every county in Ireland.

What You Can Do

-

-

-

- Don’t use moss peat in the garden. The mining of moss peat from our bogs is removing the habitat of our carnivorous plants and threatening their future.

- Go peat free in your garden by recycling all the organic material to make compost.

- When you visit a garden centre only buy peat free garden products.

-

-

Text, Photographs and Images © Irish Peatland Conservation Council, Bog of Allen Nature Centre, Lullymore, Rathangan, Co. Kildare. Email: bogs@ipcc.ie; Tel: +353-45-860133.