The Common Frog (Rana temporaria) is the only species of frog found in Ireland and is listed as an internationally important species. Frogs are protected under the European Union Habitats Directive and by the Irish Wildlife Act.

The Common Frog (Rana temporaria) is the only species of frog found in Ireland and is listed as an internationally important species. Frogs are protected under the European Union Habitats Directive and by the Irish Wildlife Act.

Frogs are amphibians which means they can survive in the water and on land. Their body is well adapted to this dual life. Their large eyes bulge out of the top of their head so the frog can keep a sharp lookout for food and danger. The eyes are very sensitive to movement. When frogs leap they draw eyes their back into their sockets to protect them from damage. Frogs have an ear drum behind the eyes and their hearing is good. Nostils in front of the eyes are used by frogs to breathe when they are on land. A frog’s skin is loose on its body and moist. Under the water they breathe through their skin. Skin colour and markings vary enormously. The basic colour ranges from a pale green-grey through yellow to a dark olive-coloured brown. The only regular markings are the dark bars across the limbs, and streaks behind and in front of the eyes. The colourful patterns on the frog’s skin help to disguise it from enemies such as rats, herons and hedgehogs. A frog can also make its skin become darker to match its surroundings. This colour change takes about two hours. Frogs have four fingers and five toes. The webbed feet are like flippers and help the frog to swim away from danger very fast. The frog’s hind legs are very muscular which helps it to swim in the water and leap on land. Each time the frog croaks, the loose skin on his throat expands. Frogs make lots of different sounds, especially in spring during the breeding season when they return to the wetland in which they were born to breed.

Frogs feed on slugs, insects, worms, spiders and similar prey, but do not predate aquatic organisms. In winter, frogs hide in frost-free refuges, under tree stumps, in stacks of turf, or in rock piles where they enter torpor until the following spring.

Frog Profile

Food: Slugs, worms, flies and other insects. The frog’s long sticky tongue is attached to the front part of the mouth, so that it can flick out to catch food.

Habitat: Damp vegetation, camouflaged ponds, hedgerows.

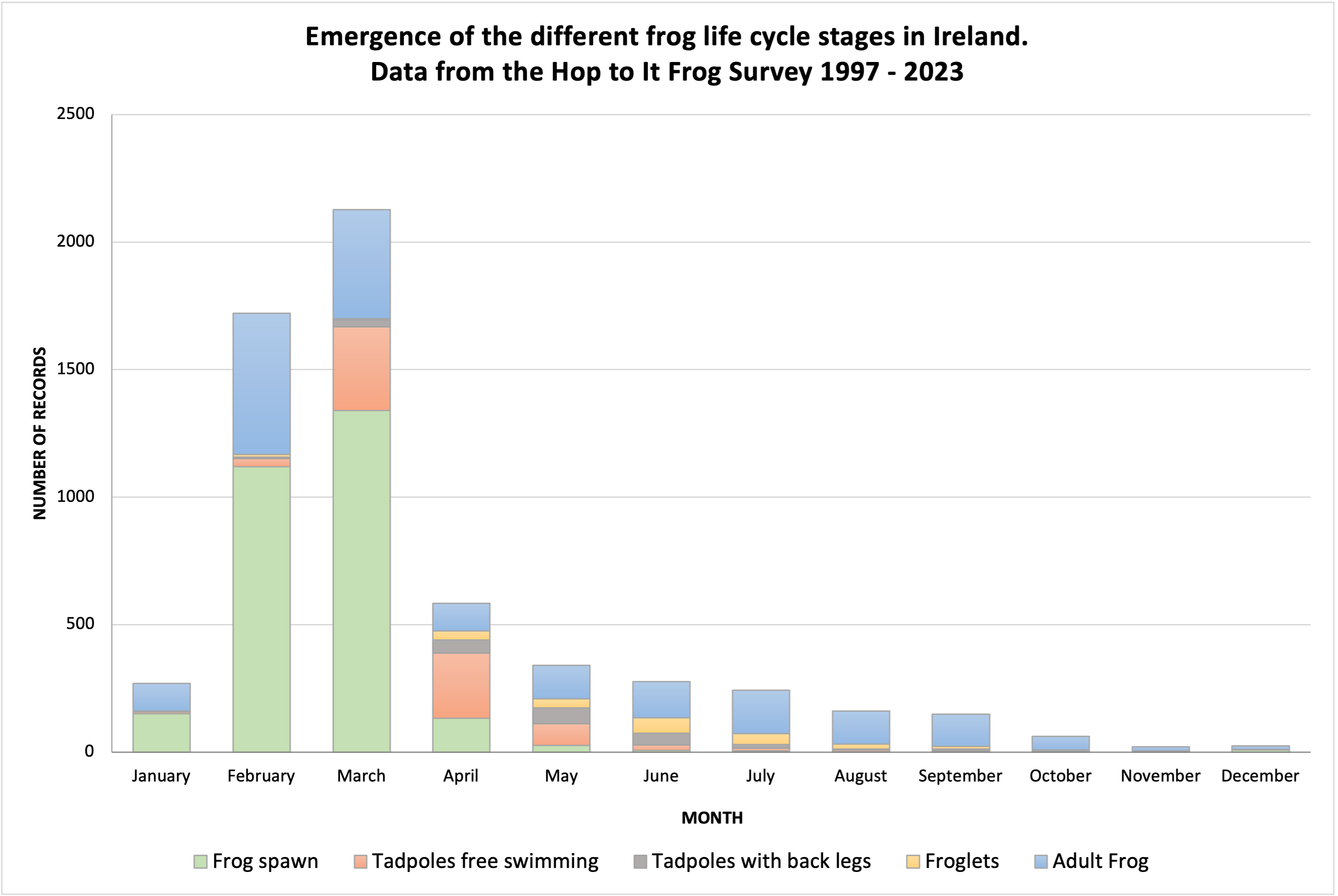

Reproduction: Breed around February and spawn around March, Tadpoles hatch and grow from April to May, Tadpoles metamorphose into froglets, and leave the pond in June/July.

Frog Life Cycle

When the adults emerge from hibernation they migrate to congregate at various breeding sites. They may travel up to half a mile to find a site where they gather in large numbers. The males always arrive first and strike up a chorus of loud croaking to attract females. Frogs do not have any elegant courtship rituals; the eager male simply grabs the nearest female as she arrives at the spawning site. Jumping onto the female’s back, the male wraps his fore limbs around her body and grips using nuptial pads, on the fore limbs – a position called amplexus.

Spawning itself can take place any time during amplexus and lasts only a few seconds. The female lays over 2,000 black eggs while the male releases sperm. The eggs are fertilised immediately and before their gelatinous capsules absorb water, swell and rise to the surface. After spawning the female usually leaves the pond, while the male often goes on to search for another mate.

Spawning itself can take place any time during amplexus and lasts only a few seconds. The female lays over 2,000 black eggs while the male releases sperm. The eggs are fertilised immediately and before their gelatinous capsules absorb water, swell and rise to the surface. After spawning the female usually leaves the pond, while the male often goes on to search for another mate.

Both male and female frogs return to the same pond year after year, probably recognising it from the smell of the water and algae.

Eggs & Frog Spawn: Each frog egg is 2-3mm in diameter and is enclosed in an envelope of jelly. When the egg is deposited in the water the jelly swells to a diameter of 8-10mm insulating the eggs from the water. The egg develops into a tadpole in 10-21 days (the higher the temperature the shorter the development time).

Tadpole: The tadpole digests the spawn jelly using a special secretion and hatches. Specific adhesive organs fasten the newly hatched tadpole to other spawn or plants in the pool. At this early stage tadpoles have no mouth, and until its mouth organs form it feeds on an internal yolk sac attached to the stomach. At approximately 2 days old the external gills, mouth and eyes are formed. At this stage it moves like a fish and begins to eat algae. At 12 days spiracles and internal gills are formed. At 5 weeks the hind legs are showing and the lungs are forming. It then has to swim to the surface of the water to gulp air. The tadpole has fleshy lips with rows of teeth for rasping away at water plants and by seven weeks it also eats insects and even other tadpoles.

Froglet: At 10 weeks the forelegs are growing. The hind legs are fully grown and the tail is reducing. At 14 weeks the tail is nearly fully absorbed. At this stage the froglets are usually starting to spend time on rocks or in nearby damp grass. Young frogs usually double in size by the following autumn and they reach sexual maturity in their third year. They can live for 7-8 years. Scarcity of food or severe cold may delay metamorphosis and overwintering tadpoles are not uncommon in northern countries.

The IPCC Hop to It Frog Data provides information on the timing of the emergence of the different stages in the life cycle of the frog (see chart for details).

Frog Habitats

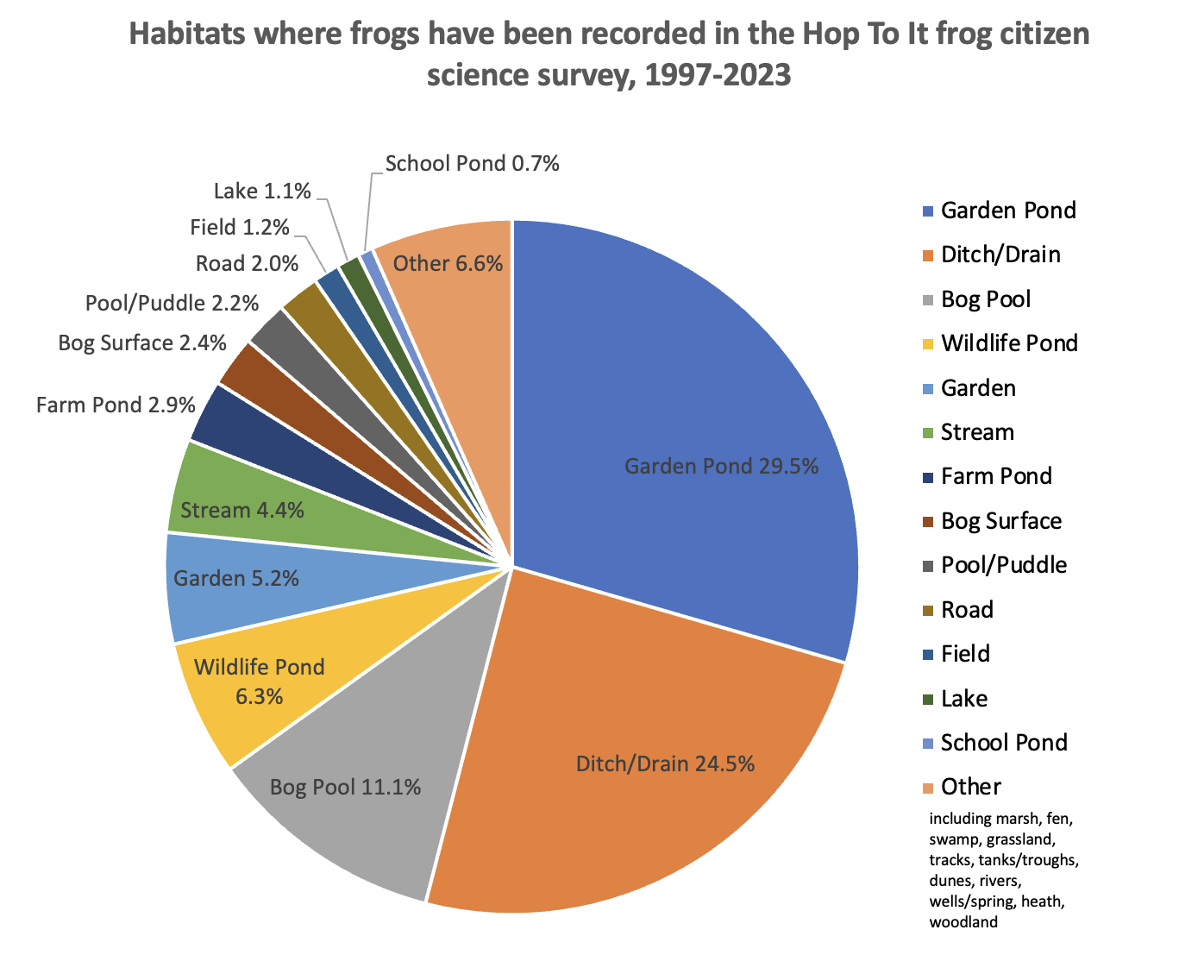

Frogs like to be near ponds which have plenty of algae and plants near the edge, usually with shallow edges so that they can easily climb out. Frogs use garden ponds, farm ponds, wildlife ponds, streams, bog pools, drains and ditches as breeding sites.

The terrestrial habitat of frogs is also important. The land around the breeding site or pond needs to be rough with long grass and some scrub to give cover for terrestrial foraging. Frogs also require habitats for hibernation. Large stones, old logs and hedgerows offer just such accommodation.

The chart below shows the various habitats where frogs have been recorded in the Hop to It Frog Survey from 1997-2023.

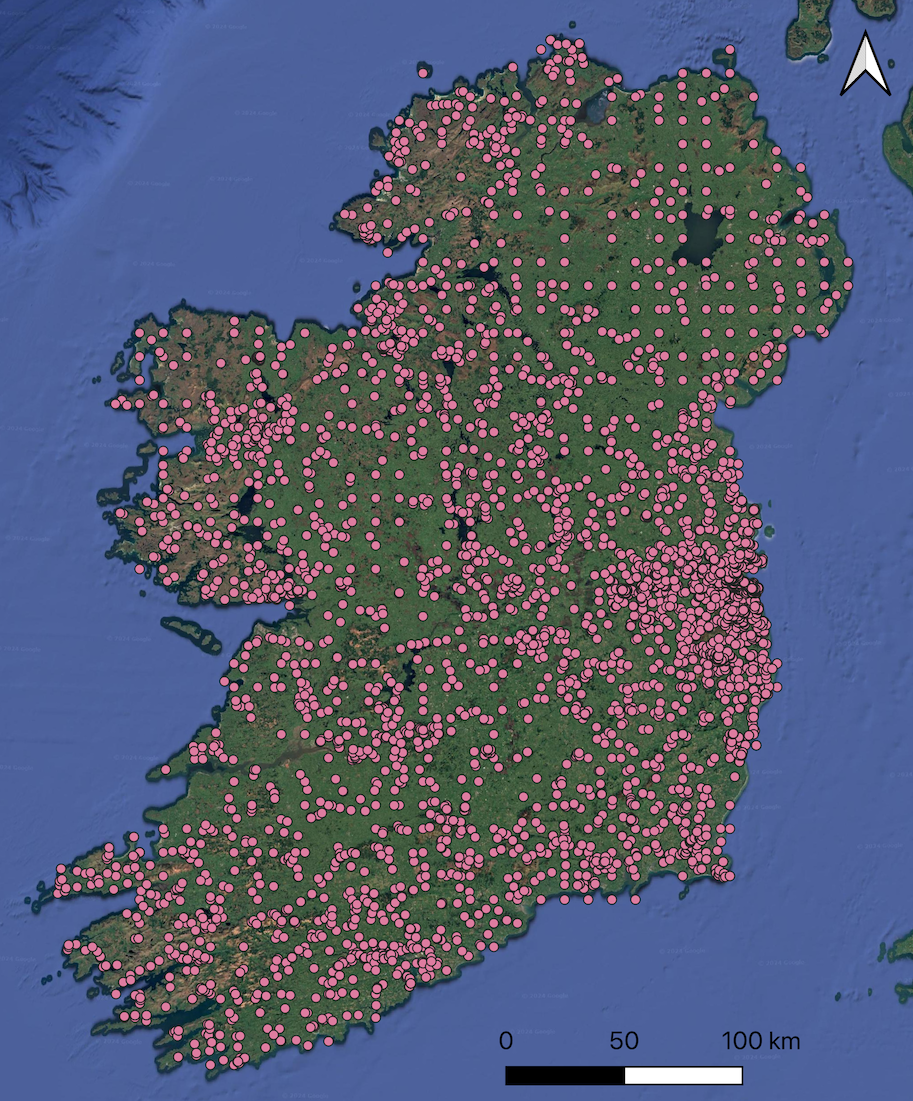

The most frequently recorded habitat in the survey is garden ponds. This may partly be because the highest number of records have been received from urban areas in Dublin and surrounding areas (see map below). However, it shows that garden ponds are important breeding habitats for frogs. Ditches, drains and bog pools are other important habitats.

Frog Distribution Ireland

The Common Frog is considered to be widespread and common in Ireland but vulnerable in the rest of Europe. Rana temporaria has an extensive range of habitat – from sea level to nearly as high as the snow line on mountains 760m up.

The map opposite shows the distribution of frog records collected in the IPCC Hop To It Frog Survey from 1997 to 2023.

Hop To It Irish Frog Survey

The first ‘Hop To It Frog Survey‘ began in 1997 and was co-ordinated by the Irish Peatland Conservation Council. The survey provided base-line information on frogs in Ireland, such as their biogeographical distribution, preferred habitats, breeding habits and success. Prior to this, surveys on the distribution of the frog in Ireland were undertaken by researchers in An Foras Forbartha, the Ulster Museum and Trinity College Dublin.

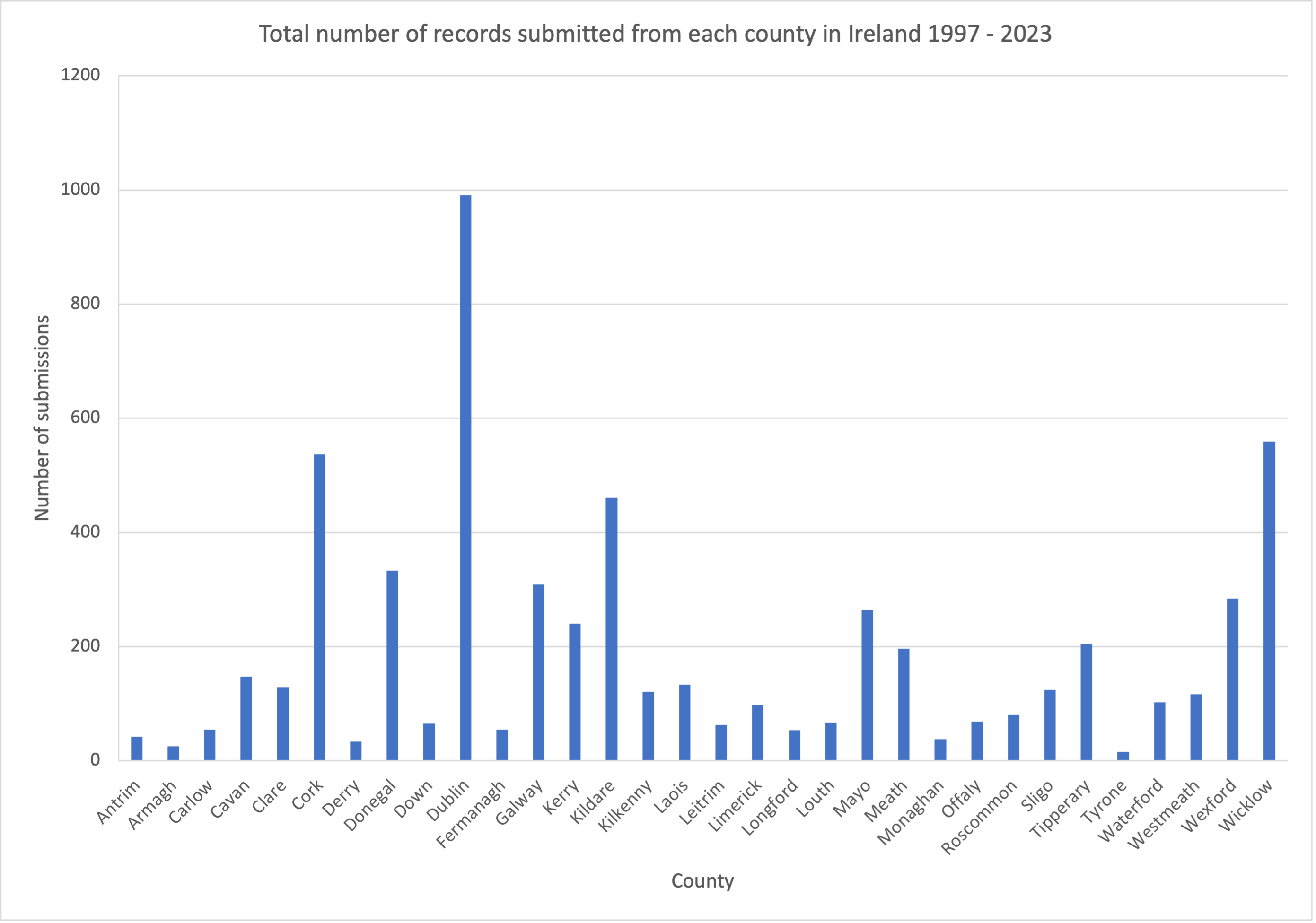

The Hop to It Frog Survey has been going strong since 1997 and by the end of 2023, the IPCC had over 6,000 records from the 32 counties of Ireland (see chart below). The records show that frogs occur and reproduce in every county in Ireland. The majority of frogs are found from 0 to 450 meters above sea level (in the Wicklow mountains). This includes all five stages in the life cycle. Our records show that frogs occur in the inner city (1.6%), city suburbs (20%) and the countryside (78%). Garden ponds are the most recorded habitat for breeding frogs, accounting for nearly 30% of all records received. This may be influenced by the fact that people could be more likely to notice frogs in their gardens than out in the wider countryside. Other important habitats are bog pools, ditches, drains, streams and puddles.

You can submit any of your frog records to the survey here.

Biodiversity Conservation

IPCC’s Hop to It Irish Frog Database is proving to be a valuable information source for protecting biodiversity in Ireland. IPCC’s frog information is being fed into County Council Biodiversity Action Plans. The information was used in the National Parks and Wildlife Service conservation assessment of the Frog in Ireland in 2008 and 2012 and by various researchers.

What Kills Frogs?

Natural Mortality: Amphibians play an important role in the food chain. During spring and summer many thousands are killed and eaten daily to nourish predators such as otters, foxes or herons. For a typical lump of spawn containing 2,000 eggs, 95% of the eggs may hatch. Only 1-5% of the remaining tadpoles make it through the metamorphosis and only a handful of the original 2,000 reach sexual maturity. If spawn is laid early in the season, hard frost may kill it, especially in shallow water. Tadpoles may also die if their aquatic habitat dries out before they have metamorphosed.

Habitat Loss: Over 50% of Ireland’s amphibian wetlands have been lost to drainage, industrial peat extraction, pollution and natural senescence in the past 100 years. The terrestrial habitat of frogs is also important. Unfortunately just as the wetlands are being drained, hedgerows are also being destroyed to make way for industrial farming methods.

Fire: An extensive danger to frogs is that of accidental fires. In any hot dry summer there are inevitably going to be accidental fires which can result in the loss of habitat. Another threat for the common frog is from deliberate regular burning of bogland in the belief that this improves the grazing for farm stock.

Pollution: Exposure to chemical fertilisers, pesticides and herbicides can cause frogs agonising deaths. Ammonium nitrate granules can kill a frog within 5 minutes. It is thought that the chemicals are absorbed into the skin and affect the balance of chemicals in the moist tissue. They then suffer a massive toxic attack.

Water polluted with heavy metals such as Aluminium, Cadmium, Zinc, Copper and Iron are toxic to frogs. Lead from car exhausts may be important even in rural areas. Acid rain can also increase the toxicity of metals in ponds causing further threats to frog populations.

UV Radiation: UV radiation has become a prime candidate for blame in the world-wide decline in frog numbers in recent years. In 1989 herpetologists from around the world reported declines in amphibian numbers. UV radiation damages DNA causing cell mutations and death. Frogs have very low levels of the necessary enzyme, photlayse, to repair the damage, and it is believed that this is a large contributor to their apparent demise.

Fatal Infections: The fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis paratises amphibians and has caused frog and toad population declines throughout the world since the 1980’s. The fungus destroys the skin pigment keratin in amphibians. Frogs infected appear emaciated and lethargic, often with abnormalities of the skin or eyes. The fungus has caused the extinction of the Costa Rican golden toad (Bufo periglenes) and serious frog kills in Panama, Australia and the U. S. The rapid spread of the fungus at 42km per year, has been blamed on ozone depletion and loss of forest cover, which change the habitats of sensitive amphibians.

Several mass deaths of frogs have been blamed on a disease known as “red leg”. A British study has uncovered a new virus – Ranavirus which is responsible for killing frogs by the hundred.

Road Migration Deaths: During a few warm, damp nights in spring, thousands of amphibians follow traditional migration routes on their way to spawning ponds. Unfortunately, hundreds can be squashed and killed by traffic on intervening roads as they make for a suitable pond.

Food and Pets: Europe imports hundreds of millions of frogs from Indonesia, India and Bangladesh, threatening some species. Millions of South African frogs have been exported to the U.S. as pets. The American bull frog, a pet in Britain is a danger to native frogs. Once these or others escape they displace natural amphibian populations by hunting them or mating and producing hybrids. The release of exotic species into the wild is an offense under the Wildlife Act.

What Can You Do To Help Irish Frogs ?

- Make a garden pond to encourage frogs to breed.

- Frogs spend most of their lives on land so give them long grass, leaf and log piles, trees and shrubs in your garden to feed and hibernate under.

- Pass on your knowledge of frogs to others.

- Do not keep endangered frog species as pets and never release a pet frog into the wild.

- Organise a clean up of rubbish from local ponds and streams.

- Take part in the Hop To It Irish Frog Survey and help us learn more about the status of frogs in Ireland. You can fill in an online survey form here.

Other Irish Amphibians

There are three native species of amphibian found in Ireland – the Natterjack Toad (Epidalea calamita), the Smooth Newt (Triturus vulgaris) and the Common Frog (Rana temporaria). The Natterjack toad is extremely rare, and is confined to a few areas in Counties Kerry and Wexford. The Smooth Newt is fairly widespread in Ireland, although it may be very local in distribution in the north-west and south-west.

The Common Toad (Bufo bufo) and Alpine Newt (Ichthyosaura alpestris) are also found in some locations in Ireland but are non-native.

Hop To It Frog Book – Citizen Science Initiative

With funding support from Local Authorities in 2019 under the Local Agenda 21 Environmental Partnership Fund and in 2020 under the Climate Environment Action Fund IPCC view IPCC’s Hop To It Frog Book online.

Text, Photographs and Images © Irish Peatland Conservation Council, Bog of Allen Nature Centre, Lullymore, Rathangan, Co. Kildare. Email: bogs@ipcc.ie; Tel: +353-45-860133.